Butterflies of Florida: the State’s Winged Wonders

A detailed, realistic close-up showing textured reptile skin morphing into butterfly wings.

🌴 From Scales to Wings: How I Fell for Florida’s Butterflies

For many years, my work focused on cold-blooded animals. As a herpetologist, I studied reptiles and amphibians — the slippery snakes, athletic frogs, and the ancient, do-not-mess-with-me gaze of gators that defined my field seasons.

Florida was perfect for that life: warm springs, shaded hammocks, and abundant sun made it easy to find reptiles and amphibians to study.

But the Sunshine State also nudged me toward a different corner of the natural world.

My path into lepidoptery — the study of butterflies and moths — didn’t begin in some remote swamp. It began at Wekiwa Springs State Park, where I worked as a park biologist and started noticing a richness of winged life I had previously overlooked.

A meeting with entomologists Randy Snyder and Mary Keim changed everything.

They invited me to join a national butterfly count, a citizen-science effort that systematically surveys butterfly populations across regions (consider linking this to the North American Butterfly Association or local count pages).

I joined out of professional duty at first — another survey to add to the park’s biological inventory — but the process of learning field techniques, watching identification methods up close, and observing these delicate insects in the light changed my perspective.

Butterflies — members of the order Lepidoptera — proved to be far more than ephemeral flashes of color. Up close, you see their intricate scales, the fine structure of a wing, and the delicate proboscis adults use to sip nectar.

Their life cycles and interactions with host plants revealed deep ecological connections across habitats.

Florida, I discovered, is much more than reptiles and amphibians: it’s a true paradise for butterflies, teeming with species and moths that offer endless opportunities for study, photography, and simple enjoyment.

In this article, you’ll find a practical guide to the best park spots, key facts about Florida’s butterfly diversity, answers to common questions, and easy actions you can take to support these insects in your own yard or community.

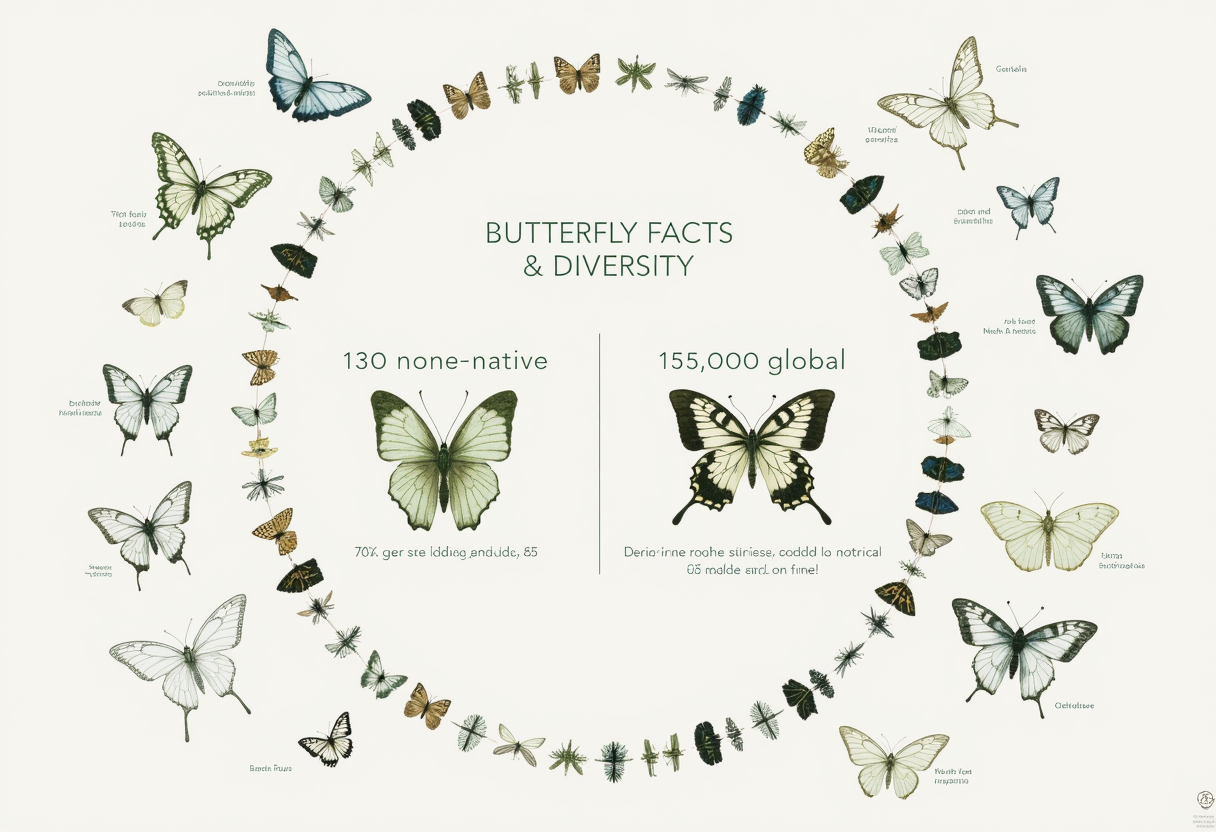

An artistic and informative graphic. The central elements are the numbers "170 native," "30 non-native," "150,000 global," "765 North America," and "3,000 Florida total Lepidoptera,

🗺️ Florida’s Premier Butterfly-Watching State Parks

For anyone eager to see butterflies in the wild, Florida’s state parks offer unmatched access to diverse habitats where butterflies and moths thrive. These protected areas supply the nectar, host plants, and sheltered microhabitats essential for every stage of a butterfly’s life—from eggs and caterpillars to chrysalis and adults—and they make excellent field sites for photographers, families, and citizen scientists alike.

Below are top Florida parks with reliable butterfly activity, quick practical notes for each site, and tips to help you spot the most species on a visit. (Consider adding park-specific links and a downloadable checklist or map to boost engagement.)

🏞️ State Park 🌸 Butterfly Vibe — Quick Notes

Florida's Butterfly Paradise (Panoramic): A wide, panoramic digital painting showcasing Florida as a "butterfly paradise.

San Felasco Hammock Preserve State Park — Shady trails and fluttering wings. This expansive preserve near Gainesville contains shady hammocks and upland forests where woodland butterflies show up along dappled trails. Best seasons: spring–fall. Key species: various hairstreaks and skippers (Lycaenidae and Hesperiidae), woodland swallowtails.

Host & nectar plants: native oaks, wildflower understory, and nectar-rich blooms along trail edges. Visitor tips: walk early morning in sunny clearings; bring water and close-focus binoculars.

Ichetucknee Springs State Park — Tubing with butterflies overhead. Known for its clear, spring-fed river, Ichetucknee also supports lush riparian vegetation that attracts many butterflies along the banks. Best seasons: spring–summer.

Key species: fritillaries and sulphurs that favor moist, flower-rich river margins. Host & nectar plants: milkweeds, willow-leaved morning glory, native asters. Visitor tips: watch riverbanks and sunny sandbars; be mindful of fragile shoreline plants while tubing.

Rainbow Springs State Park — A rainbow of species in gardens and forest. With formal gardens, natural hammocks, and aquatic edges, Rainbow Springs creates layered habitats that support a wide variety of butterflies year-round. Best seasons: spring–fall (but many species are visible in mild winters).

Key species: gulf fritillary, tiger swallowtail, and assorted skippers. Host & nectar plants: ornamental native wildflowers and garden plantings that boost nectar availability. Visitor tips: check garden beds and sunny glades; photograph perched butterflies in the morning light.

Manatee Springs State Park — Water, woods, and winged visitors. While famous for wintering manatees, this park’s floodplain forests and uplands also host a healthy butterfly community. Best seasons: year-round, with peaks in spring and fall. Key species: woodland edge specialists and generalists that exploit wet-to-dry ecotones. Host & nectar plants: riverine wildflowers, buttonbush, and native grasses. Visitor tips: walk boardwalks near wetlands for mixed assemblages of sun-loving and shade-tolerant species.

Big Shoals State Park — Whitewater and wild wings. Home to Florida’s whitewater rapids on the Suwannee River, Big Shoals offers riparian clearings and upland forests that favor sun-loving butterflies. Best seasons: spring–summer.

Key species: swallowtails and meadow species that frequent open, sunny banks. Host & nectar plants: native flowering forbs in meadows and edge habitats. Visitor tips: explore river-edge meadows in mid-morning when butterflies are actively nectaring.

Paynes Prairie Preserve State Park — Prairie skies and butterfly spies. This large savanna and wetland complex near Gainesville supports prairie-adapted butterflies as well as wide-ranging species that use open grasslands.

Best seasons: spring–fall. Key species: hairstreaks, fritillaries, and rarer prairie specialists. Host & nectar plants: native prairie forbs and milkweeds. Visitor tips: bring sun protection and scan grasses for perching butterflies; early spring wildflower blooms are especially productive.

Crystal River Preserve State Park — Coastal charm with fluttering flair. Along the Gulf Coast, this preserve protects coastal forest, salt marsh, and tidal creeks—habitats that support a distinct coastal butterfly fauna.

Best seasons: spring–fall. Key species: coastal specialists and migrants that use maritime host plants. Host & nectar plants: salt-tolerant wildflowers and dune-edge plants. Visitor tips: explore maritime hammocks at low tide or on calmer days for greater butterfly activity.

Little & Big Talbot Islands State Parks — Barrier island butterflies on vacation. These undeveloped barrier islands near Jacksonville feature dunes, maritime forests, and salt marsh, serving as stopover and breeding habitat for migratory butterflies. Best seasons: migration periods (spring & fall) and summer breeding.

Monarch Migration: Florida Stopover: A powerful, evocative illustration from an aerial or slightly elevated perspective, depicting a significant gathering of Monarch butterflies in a Florida setting during migration.

Key species: migratory monarchs and resident coastal species. Host & nectar plants: seaside goldenrod, coastal asters, and other dune flora. Visitor tips: respect sensitive dune vegetation and watch sheltered hammocks for resting butterflies during migration.

Marjorie Harris Carr Cross Florida Greenway — A corridor of butterfly movement. Stretching across central Florida, this conservation corridor links sandhills, wetlands, and forests—critical for species dispersal and genetic exchange. Best seasons: year-round, with seasonal peaks.

Key species: a mosaic of sandhill and wetland specialists along the corridor. Host & nectar plants: diverse mosaic including native wildflowers and host shrubs. Visitor tips: cover more ground to find habitat transitions; bring an insect field guide and record sightings for citizen science projects.

These parks collectively reflect Florida’s mosaic of butterfly habitats: from nectar-rich prairie meadows to shaded hammocks where light-filtered clearings reveal perched butterflies.

Whether you’re seeking the striking colors of a Zebra Heliconian or the migratory spectacle of monarch butterflies, these sites offer high potential for sightings and learning.

What to bring: a field guide, close-focus binoculars, water, sun protection, and, optionally a notebook or app (iNaturalist) to record sightings. When photographing or approaching butterflies, move slowly, avoid crushing host plants, and leave caterpillars and chrysalises undisturbed.

Pro tips for more species: visit sunny clearings mid-morning to early afternoon, target areas with abundant native flowers, and learn a few common host plants so you can find caterpillars as well as adults.

If you want, download the printable checklist (suggested addition) for each park and consider joining local butterfly counts to support monitoring efforts.

🧠 Butterfly Facts That Illuminate Their Significance

Beyond their obvious beauty, butterflies are powerful indicators of ecosystem health and subjects of serious scientific study. Their population trends, seasonal movements, and life-cycle changes provide useful data for conservation biologists, land managers, and citizen scientists tracking environmental change.

Florida’s role in North American lepidoptery is notable: the state’s varied climates and habitats support a rich assemblage of Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths), making it a key region for both diversity and monitoring efforts.

: A close-up, artistic photo-realistic shot depicting the intricate interaction between a butterfly and a native Florida wildflower.

Key numbers at a glance: approximately 170 native butterfly species recorded in Florida, plus roughly 30 non-native or vagrant species; globally the order Lepidoptera includes an estimated 150,000 named species (the majority are moths); North America contains about 765 recognized butterfly species; and when butterflies and moths are combined, Florida’s Lepidoptera list approaches 3,000 species. (Replace with specific citations in the rewrite: Florida Museum checklist, Butterflies and Moths of North America, and NABA.)

A few notes on those figures: “butterflies” comprise a visible, day-active portion of Lepidoptera, while moths represent the larger taxonomic majority.

That distinction helps explain why the global Lepidoptera number is so large, even though butterflies are a smaller subset. In practical terms, both butterflies and moths contribute to pollination networks, food webs, and nutrient cycles across Florida’s habitats.

Representative species and context. Florida’s list ranges from large, charismatic species like the Giant Swallowtail (Papilio cresphontes), one of North America’s largest butterflies,

to widespread introduced species such as the Cabbage White (Pieris rapae), which established globally after arriving from Europe. These examples illustrate both native diversity and the ecological effects of non-native introductions.

Why this matters: butterflies and moths serve as bio-indicators because their life stages (eggs, caterpillars, chrysalises, adults) respond quickly to habitat change, chemical exposure, and climate shifts.

Monitoring changes in species presence, abundance, and range can signal broader environmental trends long before larger-scale impacts become apparent.

Butterflies vs. moths — a short comparison: butterflies are typically diurnal and conspicuous, often with bright colors and clubbed antennae; moths are usually nocturnal or crepuscular, show a wider variety of sizes and shapes, and carry many more species worldwide.

Both groups, however, share scales on their wings and similar life cycles involving caterpillar and pupal stages.

For readers interested in exploring the data further, I recommend consulting state checklists and regional databases (Florida Museum, Butterflies and Moths of North America, and NABA). Adding simple records—photos with date and location—to platforms like iNaturalist helps researchers refine species lists and track long-term changes in Florida’s butterfly community.

Elevated view of hundreds of Monarchs clustered in trees with milkweed and chrysalises visible in the foreground. Alt text: "Monarch butterflies clustered in Florida during migration." Filename: monarch-migration-florida.

🤔 Addressing Common Queries About Florida’s Butterflies

Seeing butterflies often sparks questions about how common they are, when to look for them, and what roles they play in local ecosystems. Below are concise, field-tested answers based on years of observation in Florida.

Are butterflies common in Florida? Yes. Butterflies are widespread across the state—in natural areas, suburban yards, and even coastal dunes. Florida’s warm, subtropical to tropical climates, diverse habitats, and abundance of nectar and host plants support many butterflies year-round. You’ll encounter both resident species and seasonal migrants across parks, gardens, and roadside wildflower patches.

Do butterflies have a season in Florida? Not in the strict temperate sense. Peak activity is usually spring through fall when temperatures and flower abundance climb,

but in South Florida and mild winters, you can see butterflies on most days. Many species produce multiple generations per year, so you can find eggs, caterpillars, chrysalises, and adults across seasons.

What invasive butterfly should I know about? The Cabbage White (Pieris rapae) is a widespread, introduced species in Florida. Originating in Europe, its larvae feed on brassica crops and related cultivated plants, making it common in gardens,

farms, and disturbed habitats. While not catastrophic compared with some invaders, its generalist habits and abundance have altered local insect-plant dynamics in places.

Do monarch butterflies migrate through Florida?

Absolutely. Florida is part of the eastern North America migratory route for Monarchs (Danaus plexippus).

Large numbers pass through Florida during the fall migration on their way to overwintering sites in Mexico; some South Florida populations may breed year-round and show less migratory behavior. Florida’s milkweeds (Asclepias spp.) and nectar sources are critical stopover and breeding resources for migrating and resident Monarchs.

Quick backyard tips to help butterflies (and monarchs): plant native nectar flowers and host plants (milkweeds for monarchs, native asters, coreopsis, and blazing star for many species); avoid broad-spectrum pesticides that kill caterpillars and beneficial insects; provide sunny sheltered spots and shallow puddling areas for minerals; and leave some host-plant foliage for caterpillars and chrysalises.

Fast ID tips: Cabbage White—plain white wings with small dark spots (adults). Monarch—distinctive orange-and-black wings; caterpillars are striped and feed on milkweed. Learning a few common host plants helps you find caterpillars and eggs as well as adults.

For deeper reading and current region-specific guidance, consult resources such as Monarch Watch, the Florida Native Plant Society, local extension services for invasive-species notes, and citizen-science platforms like iNaturalist or the North American Butterfly Association (NABA) for local counts and monitoring events.

A subtly evocative image depicting the author's shift in focus. A silhouette or partially obscured figure (representing the herpetologist) stands in a lush, green Florida landscape (perhaps a mix of wetland and upland forest).

🧡 Why Butterflies Matter (Even to a Herpetologist)

Shifting my focus from the textured scales of reptiles to the delicate wings of butterflies wasn’t just a change of subjects—it revealed deeper ecological connections I hadn’t appreciated. Butterflies and moths (order Lepidoptera) are integral parts of healthy ecosystems, and their presence tells us a lot about habitat quality.

First, butterflies are important pollinators. As adults use their proboscis to sip nectar from flowers, they move pollen between plants and help fertilize many native wildflowers—and in some cases, contribute to the pollination of food crops.

While bees often get the spotlight, butterflies provide complementary pollination services across a range of plant species, especially those with long corollas suited to a butterfly’s proboscis.

Second, butterflies are excellent bio-indicators. Their life cycle stages—eggs, caterpillars, pupae (chrysalises), and adults—are sensitive to habitat loss,

pesticide exposure, chemical runoff, and climate shifts. Declines in local butterfly populations frequently foreshadow broader ecosystem stressors that can affect other insects, birds, and plant communities.

Third, butterflies matter for food webs: caterpillars are a vital food source for birds and small mammals, and adult butterflies support predators such as praying mantises and spiders.

Their scales, wing patterns, and flight behaviors reflect evolutionary responses to predators, host plants, and microclimate conditions—details that reveal the complexity of ecological interactions.

Concrete examples: the Giant Swallowtail (Papilio cresphontes) is a large Florida butterfly that helps illustrate pollinator value and landscape connectivity; the introduced Cabbage White (Pieris rapae) demonstrates how non-native butterflies can become ubiquitous and affect agricultural plants.

Observing both adults and caterpillars at host plants helps you see the full life cycle and ecological roles these insects play.

How you can help — simple actions with measurable results:

Plant native nectar flowers and host plants (milkweeds, coreopsis, blazing star, native asters) to support multiple butterfly life stages.

Avoid broad-spectrum pesticides and reduce chemical use—these can kill caterpillars and pollinators outright or accumulate in the food chain.

Provide sunny, sheltered spots and a shallow “puddling” area (a damp sand patch) for mineral uptake.

Participate in butterfly counts and log observations on platforms like iNaturalist or eButterfly to support monitoring and research.

Local restoration projects—community meadows, roadside wildflower plantings, and schoolyard gardens—have shown measurable increases in butterfly abundance and species richness when native plants are used and pesticides are minimized.

An artistic, conceptual map or visual representation of the "Florida Unwritten Butterfly Trail."

Including a few host-plant species in a yard or community patch can produce visible results within a year: more caterpillars, more chrysalises, and more adults visiting flowers.

For readers interested in technical sources, include state and regional references (Florida Museum Lepidoptera checklist, university extension publications on pollinators and pesticide impacts, and NABA/Monarch Watch guidance) in the final rewrite to support these claims.

Together, small actions by gardeners, land managers, and volunteers can bolster Florida’s butterflies and the broader lepidoptera community they represent.

📣 Call to Action: Discover Florida's Butterflies

Feeling inspired to explore Florida’s butterflies? Grab a field guide, a pair of close-focus binoculars, and head to a nearby park or native-plant garden. Observing butterflies—adults and caterpillars alike—gives you a front-row seat to life cycles, pollination, and seasonal migration.

Start with the "Florida Unwritten Butterfly Trail" (an informal, field-tested list of high-value sites) or your local state park pages to plan visits to spots rich in nectar and host plants.

For easy identification and record-keeping, use apps such as iNaturalist or eButterfly to upload photos (date and location help researchers) and to contribute to long-term monitoring.

Join a local butterfly count or sign up with the North American Butterfly Association (NABA) to turn casual observations into valuable data. If you prefer backyard action, plant native flowers and host plants—milkweed for monarch butterflies, coreopsis, blazing star, and native asters—to attract many butterflies and provide resources for caterpillars and adults.

Avoid broad-spectrum pesticides and provide sunny, sheltered spots and a small damp patch for puddling; these simple steps support pollination and boost local insect diversity.

Share your sightings and stories: post photos to the comments below, tag us on Pinterest, or add your records to iNaturalist under a Florida project.

If you have a favorite park or a memorable migration moment—perhaps watching monarchs on the move—your note could help other readers pick a spot and time to see similar events.

"Thanks for reading. Until next time, keep exploring Florida's peculiar charm!"

Earl Lee